I found myself oversimplifying again, fixating on medium positions to address more muscle at once.

To start, I felt the wide-grip flat bench press gave full chest development. However, soreness from passive tension or the stretch, in the upper half, did not lead to tenderness from active tension (which stimulates most growth) in the lower pecs.

To hit the whole chest, you need more. Done strictly, each angle of the bench press hits the muscle differently. 0° degrees hits the sternocostal part and ~30° degrees hits the clavicular head.

To be fair, studies aren’t always clear. Some research, yet few among the majority, show little difference among pressing variations. Yet we engaged in bodybuilding know this to be false, at least for growth.

The rear deltoid aligns flatter than the lats at anatomical position. This could explain less activation on seated rows for the former muscle with a typical range of motion that avoids hyperextension. So I was wrong for rear delts too.

It seems that muscle fiber orientation accounts for why everything isn’t hit equally. Aligning resistance more directly with the fibers appears best.

However, I thought standing heel raises would hit both the gastrocnemius & soleus. This exercise undertrains the latter muscle. Wrong again…

In other cases then, the nervous system must play a vital role.

It seems our bodies emphasize muscle parts that generate the most force for that motion. Size affects this but it changes based on internal moment arms, or leverage, too. They select prime movers, and other muscles contribute merely as synergists.

Maybe this aims to prevent unwanted force at other joints or limit energy use in the long run as well, but it’s reality however it works.

As Vince Gironda said, “I have found that man’s logic and nature’s logic are totally different.”

We may hope additional muscles are involved yet this means finer control over where we grow.

When you analyze both the experiences of bodybuilders plus the science involving EMG, MRI or hypertrophy itself, much variety in bodybuilding is supported.

Even seemingly minor changes like how you point your feet, or rotate your hips, on heel raises matter.

Perhaps as a student of bodybuilding, this is all obvious to you. It’s a good reminder that contrarians (like myself often) are mostly wrong! Always begin from the established knowledge base in any field.

Once you admit that bodybuilding requires diverse muscle action, can you still find ways to reduce the number of exercises?

I believe so…

Emphasize compound exercises.

Exercises allowing heavy weight, namely compound, have more even strength curves. This means effort you expend is more equal throughout the range of motion. This matters because some muscles activate more during specific portions of a movement.

Bench pressing involves the serratus anterior, which performs scapular protraction, better than dumbbell flyes due to higher overload around lockout.

Bent-over rows hit the lats better than bent-over lateral raises, which focus on the rear deltoids & middle trapezius. Overload is greater until surpassing the midpoint where the lats begin lacking the proper angle of pull.

These big exercises are safest on the joints too, barring very low reps or extreme ranges of motion, emphasizing compression over shear. They may work better for single-joint muscles.

Yet remember that compound exercises are incomplete, failing to adequately work multi-joint muscles.

Still, if you can pick either a compound or an isolation exercise to focus on a muscle, you’ll likely have better overall results with the compound.

Use enough range of motion.

Big exercises with the most range of motion hit more muscle intensely, often in ways easy to overlook.

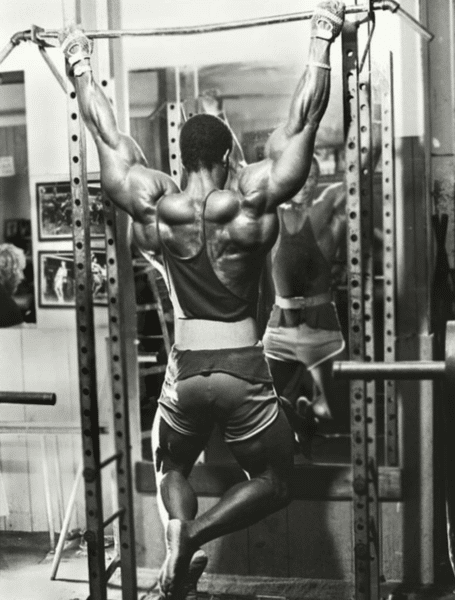

The pull-up targets the outer lats but also hits the middle lats, lower traps & lowest outermost chest as you approach your chin and beyond.

Many bodybuilders stop at 90° on lateral raises to focus on the middle delts. Going higher though recruits the upper traps as you both elevate and have more upward rotation.

Shoulder hyperextension, or going past the plane of your body on bent-over rows, focuses on the posterior delts. This is important since they don’t help as much on shoulder extension.

But never harm yourself with too much range of motion. On squats, for instance, there is no reason to go below parallel or sometimes even there for that matter. In most cases, you just need to move across the midpoint sufficiently, not to the utmost ends.

Use near-medium grips & stances.

Medium positions let you hit all the involved muscles thoroughly and also tend to be safest again.

You’ll notice that EMG for the lower chest, anterior deltoid & single-joint triceps heads are similar on the bench press.

When you grip widely on rowing, you’ll emphasize scapular retraction, working the mid & lower traps. Going narrower like on T-bar rows hits the lats & rear delts increasingly. By taking a middle position though, you’ll work both muscle sets about evenly.

Competition seems to occur among muscles at the same joint, not others. What I mean is that rows may hit the lats better than the rear delts, and vice versa with bent-over lateral raises, but the traps get involved either way.

Evaluate this in context of your whole program. It may be sensible to go slightly wider on the bench press when including arm extensions. Ensure the exercise hits the intended muscle foremost.

Combine muscle actions.

While this happens naturally on compound exercises, an unusual exercise variant comes to mind.

Twist your wrists so your palms face the ceiling, beginning at neutral, on dumbbell curls. This is done most easily on an incline bench.

By using an offset grip or plates also, you challenge arm supination alongside elbow flexion. This not only hits the medial fibers for peaked biceps but also the brachioradialis & brachialis hardest while your hands are neutral.

I like to do scapular protraction for the serratus anterior on triceps extensions. It’s the ideal weight and doesn’t feel disruptive like when pressing, which also emphasizes horizontal adduction. I’ll hold at the very top for a few seconds.

You may get similar benefits from hip flexion with knee extension on sissy squats, and shoulder extension with arm extension on the pullover-and-press. Experiment to discover worthwhile combinations.

Orient in, out & forward.

Generally, orienting the most distal part of your limb outward stresses the inner part of the working muscle, while vice versa stresses the outer part.

Consider rotating the hips externally or internally on both heel raises and leg curls, which has your feet pointing either out or in respectively.

Per Tesch confirmed this technique in his book Target Bodybuilding, using MRI to support that these positions matter even for quads on leg extensions and biceps heads on arm curls.

If you do 3 working sets, try doing each set with a different orientation, going neutral on the final set.

My experience is that orientation matters less so for extensor muscles (triceps & quads) but helps with flexor muscles (biceps, hamstrings & calves).

Move throughout more degrees of freedom.

While unusual, Vince Gironda suggested a swinging motion on lateral raises at the top to work the full middle deltoid.

Vince also did a scooping motion on flyes to hit each chest fiber within the active portion.

This isn’t as proven as other tips here, but the existence of neuromuscular compartments like the deltoid having at least 7 functional segments seems to indicate it would help!

Rotate exercises.

You don’t need to apply the same exercises every session, just often enough to make progress.

Both squats & stiff-legged dead-lifts hit the glutes yet have unique advantages for the single-joint quads & multi-joint hamstrings respectively.

If you train your core, you could alternate sit-ups or crunches with leg raises, each covering the whole rectus abdominis yet having upper versus lower emphasis.

You can rotate less important accessory movements like dorsiflexion, forearm & neck exercises too as they may be needed less often, if at all.

Choose efficiently otherwise.

All exercises give indirect work for some muscles that could provide enough development.

Both lateral raises & reverse curls involve the forearm extensors, which may remove the need for reverse wrist curls. Heavy pulling & curls alone may be sufficient for general forearm growth.

The upper traps are involved in many exercises, with these muscles inserting into the rear of your neck. That may be enough to have your neck match the rest of your body.

Keep in mind that isolation exercises can be more efficient when viewed holistically.

For example, leg extensions address the whole quadriceps, including the multi-joint rectus femoris, while squats or leg presses only hit the single-joint vasti.

Avoid training some muscles.

In the past, I was obsessed with the concept of balance. I did this both from a misguided fear of injury and a psychological quirk of finding it “elegant.” This last reason has especially led to my dumbest ideas.

So when I squatted, I also had to do a leg raise to work the antagonist muscles.

However, the body evolved for large muscles to lift heavy loads.

Muscles like the hip flexors, abs, tibialis anterior and so on aren’t really meant to perform this role. They have little growth potential.

Furthermore, while pursuing the classic old-school bodybuilding physique, you’d avoid working quite a few muscles by design.

You may ignore training the core, except possibly before a contest, to ensure a thin waistline.

Inner thigh & outer hip muscle growth were avoided to prevent turnip-shaped thighs along with the appearance of a thick waist area.

Obliques were almost never trained, excepting some high-rep broomstick twists for toning.

Shrugs were rarely done for the upper traps, which detracted from the illusion of shoulder width.

You worked forearms & neck as needed for a complete look.

Direct front delt work through exercises like overhead pressing or front raises is often unnecessary. Horizontal pressing hits them well since the arms remain abducted.

These decisions are ultimately personal, but determine if you truly need an exercise at all!

Why Get More From Less Anyway?

For me, reducing exercises per workout not only saves time, but since I use heavy weight with plenty of rest between sets, it felt necessary. I could focus & recover better, yet grow exactly where I wanted through enough sets.

However, modern research seems to imply that if you can handle more volume, you’ll earn additional muscle growth.

I pondered that since our sarcomeres, or the basic contractile units of muscle, were nonuniform yet had an ideal length for active tension that, in theory, this would justify variation at the smallest level.

However, does different mean significant?

It seems the whole muscle adjusts to whatever length you train it. This favors working muscles hardest as somewhat elongated lengths to encourage more total tension from active & passive.

Ultimately, there are pros & cons with every approach. “Having it all” is not realistic. We indulge in wishful thinking, distorting our choices to be beneficial in all ways.

We must admit then if reducing exercises simply means suboptimal bodybuilding.

Perhaps your lats fail on rows before the delts get worked in hyperextension, since most of the range emphasizes them. Alas, you may correct this by simply adding bent-over lateral raises!

Yet progressive overload, at least covering every muscle desired, is the most important factor.

Even pull-ups & dips build arms despite the biceps & triceps working suboptimally, and some have impressive arms from these alone.

If you can tolerate a lot of exercise & variety, you’ll achieve exceptional results. Many top bodybuilders pursue this strategy successfully.

For us natural, longtime trainees that have become quite strong, you may find that efficiency in bodybuilding exercises is best when considered over the long haul… and these methods will hopefully aid you.